Revealing the hidden structural diversity of lipids

Exploring next-generation

lipid isomer analysis

Dr. Hidenori Takahashi, Shimadzu Corporation

Conventional MS/MS techniques struggle to determine the positions of carbon–carbon double bonds (C=C) in lipid molecules, making it difficult to distinguish structural isomers. A researcher set out on an ambitious path to develop a more effective way, and one that remained compatible with existing LC-MS workflows and applicable to both ESI and MALDI platforms.

Lipids are vital biomolecules found in every cell of the body and are involved in membrane structure, signal transduction and energy storage. Because of this, they are important in a variety of fields, including nutrition, cosmetics, pharmacology and medicine. For instance, understanding and identifying lipids plays a major role in drug delivery and therapies and helps with the diagnosis and monitoring of medical conditions, ranging from high cholesterol to cancer.

Lipid structural isomers are molecules with the same chemical formula but different arrangements of atoms and arise from variations in carbon–carbon double bond (C=C) positions, sn-positions, and cis/trans configurations.[1] In particular, C=C positional differences, such as those defining omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, are associated with diverse biological functions and diseases.[2]

Ways to analyze lipids

Although gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) has been widely used for fatty acid analysis, derivatization to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) often results in the loss of lipid class-specific information. That is, since fatty acids are cleaved and methylated from a mixture containing both complex lipids and free fatty acids, it is not possible to determine whether the resulting fatty acids originate from free fatty acids or from specific complex lipids. For example, if oleic acid FA 18:1 (n-9) from phosphatidylcholine (PC 18:1) increases in response to a biological trigger, while oleic acid FA 18:1 (n-9) from phosphatidylethanolamine (PE 18:1) decreases, the net change in oleic acid FA 18:1 (n-9) detected by GC-MS cannot be accurately measured.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS), on the other hand, enables intact lipid analysis but lacks structural detail using conventional low-energy collision-induced dissociation (CID), especially for C=C positions. To address this, novel dissociation techniques have been developed, including ozone-induced dissociation (OzID) and electron-based methods such as EIEIO (electron impact excitation of ions from organics).[3–4] However, these approaches face limitations in selectivity as well as instrumentation complexity.

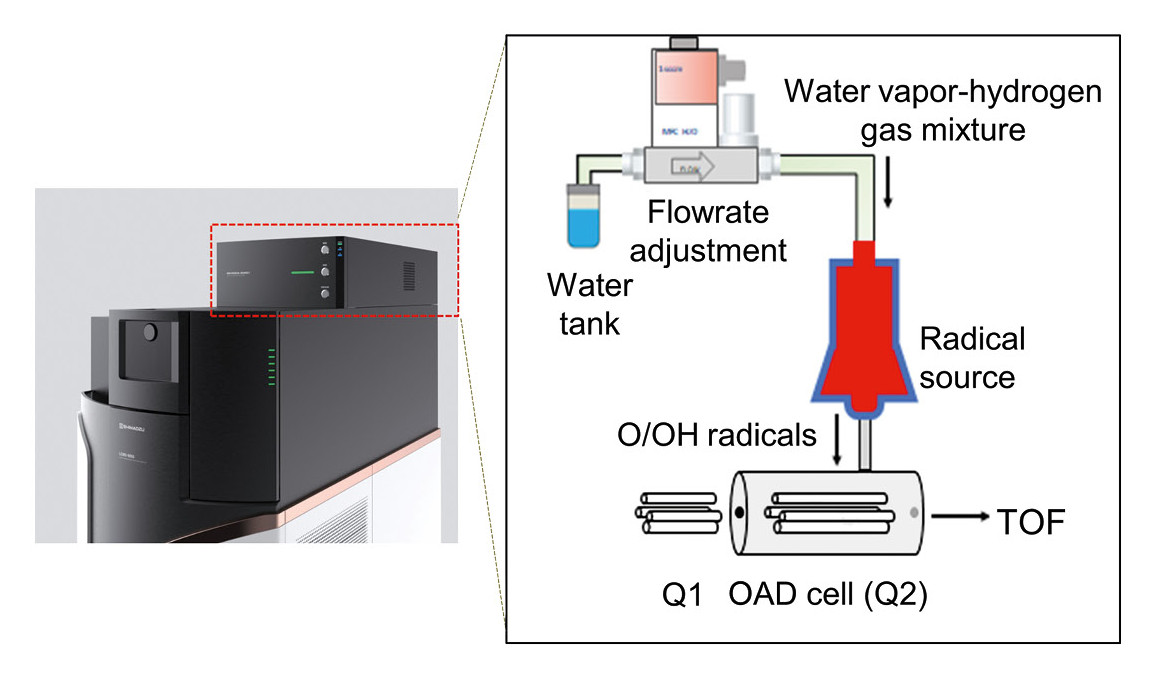

In the Shimadzu lab of Koichi Tanaka (Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 2002), a new ion dissociation method had previously been developed – Oxygen Attachment Dissociation (OAD) – which utilizes neutral atomic oxygen (O) and hydroxyl radicals (OH•) for radical-induced fragmentation.[5] Radicals are generated by microwave discharge of a water vapor and hydrogen gas mixture under vacuum (Figure 1). Since O/OH• radicals are a charge-neutral species, they are unaffected by electric fields and can be introduced directly into the CID cell (Q2) of a quadrupole mass spectrometer. They do not alter ion charge states, making the method broadly applicable to singly charged or negatively charged ions. Conventional CID can still be performed by simply switching the collision gas.

The question though was whether – and how – OAD could be applied to lipid structural isomers.

A new method for an old problem

To demonstrate the applicability of OAD for lipid structural analysis, a researcher at the Tanaka lab analyzed human plasma (NIST SRM 1980, Millipore Sigma) following extraction by the Bligh and Dyer method. Extracts were dried under nitrogen and reconstituted in methanol. LC separation was performed on a Nexera UHPLC system (Shimadzu) using a C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm) at 45 °C and 0.3 mL/min. Mobile phase A was ACN:MeOH:H₂O (1:1:3, v/v/v), and B was IPA, both containing 5 mM ammonium acetate and 10 nM EDTA. The total analysis time, including column equilibration, was 25 minutes, and the details followed those described in reference.[6] MS analysis was conducted with an LCMS-9050 Q-TOF (Shimadzu) equipped with the OAD Radical Source I (Shimadzu) in ESI mode.

Achieving differentiation of lipid isomers based on C=C position

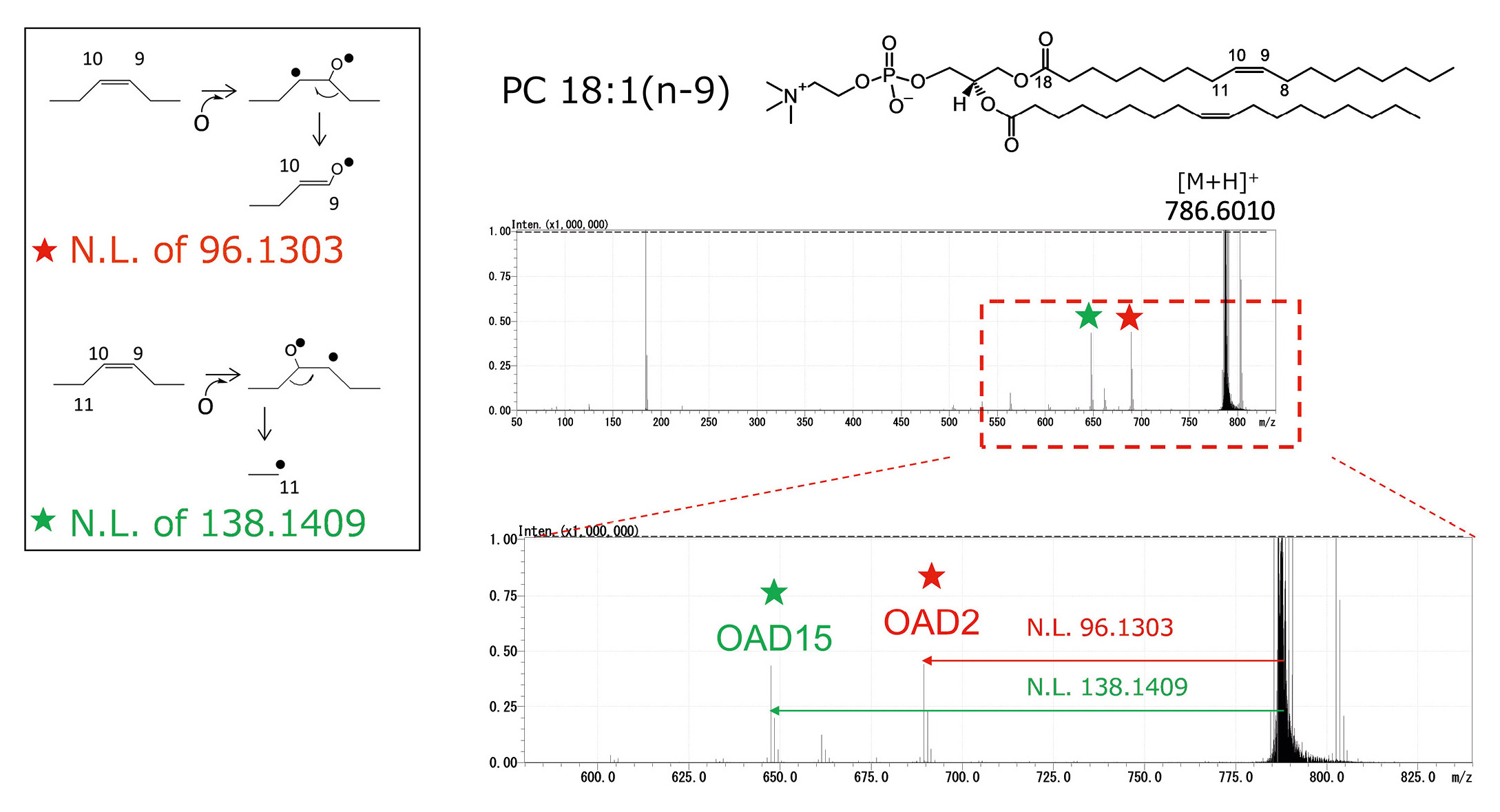

Figure 2 shows the OAD-MS/MS spectrum of the target lipid PC 18:1(n-9)_18:1(n-9), where “PC” denotes the phosphatidylcholine lipid class, “18” indicates the number of carbons in each acyl chain, “:1” indicates the number of C=C bonds, n-9 specifies the C=C position relative to the methyl terminus, and the underscore “_” separates the two acyl chains. OAD induces selective fragmentation targeting the C=C bond, resulting in two characteristic fragment peaks (OAD2 and OAD15), as shown in Figure 2. These peaks are not observed in conventional CID spectra. Details on the definition and naming of OAD peaks are provided in Uchino et al.[6] Table 1 summarizes the neutral losses corresponding to OAD fragments for each C=C position.

In targeted analysis, these predicted OAD neutral losses can be preregistered in a compound table, and extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) can be used to differentiate structural isomers. Moreover, when collision energy (CE) is applied simultaneously in OAD, CID-type neutral losses of acyl chains can also be detected.[7] These neutral losses enable the identification of acyl chain length and the number of C=C bonds.[8] Thus, the combination of OAD- and CID-derived fragments allows comprehensive structural elucidation of lipids, including C=C positional information.

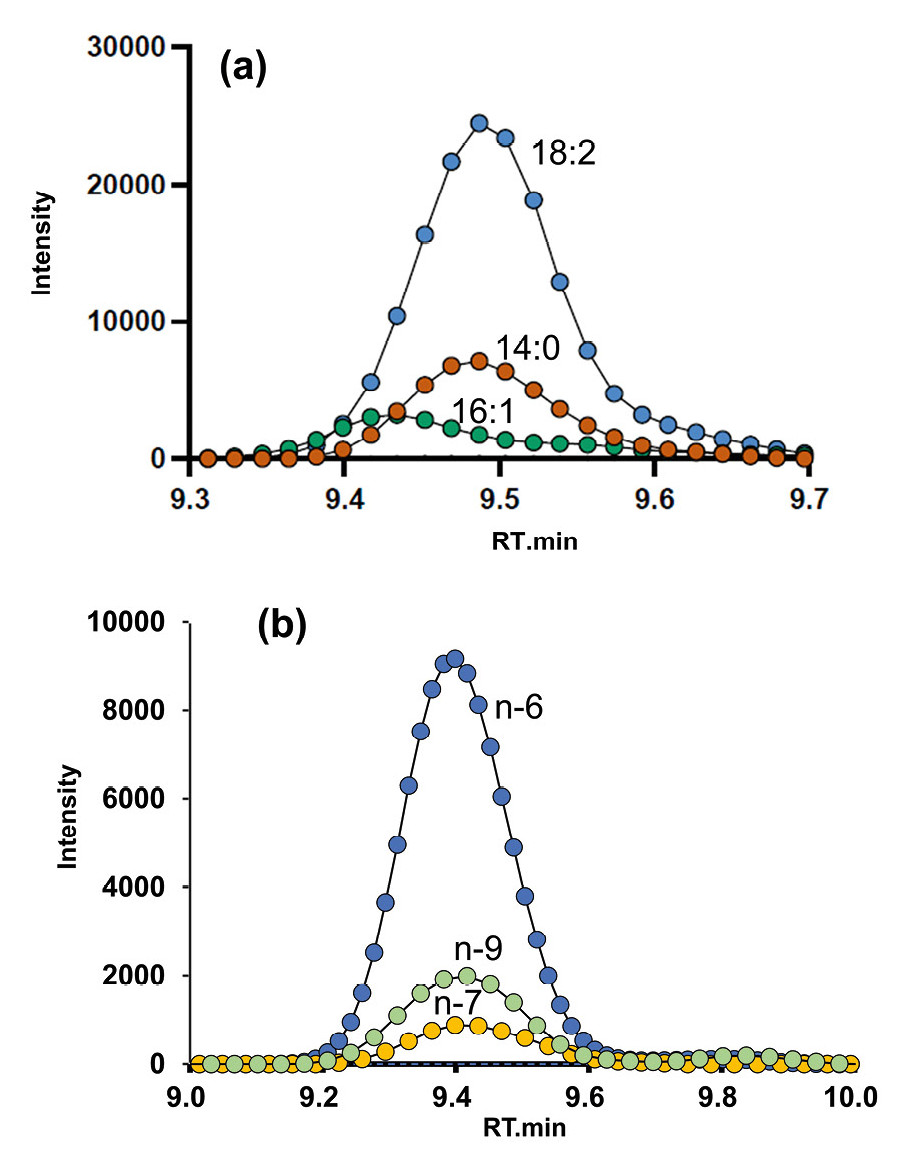

Figure 3 shows the XICs of PC 32:2 ([M+H]+ = m/z 730.539) obtained using OAD. “32:2” indicates that the two acyl chains contain a total of 32 carbon atoms and two C=C bonds. Figure 3(a) shows the XIC for CID-based acyl chain losses, while Figure 3(b) displays the XICs for OAD-neutral losses corresponding to different C=C positions. Based on Figure 3(a), possible acyl chains such as C18:2, C16:1 and C14:0 were inferred, with structural candidates including PC 18:2_14:0 and PC 16:1_16:1.

From Figure 3(b), C=C positions at n-6, n-7 and n-9′(where ′ indicates the second C=C from the methyl terminus) were detected. Combining the information from both figures, the acyl chain compositions were determined as PC 18:2(n-6, 9)_14:0 and PC 16:1(n-7)_16:1(n-7).

In a previous study, the sensitivity and quantitative performance of OAD were evaluated using a deuterium-labeled internal standard, PC 15:0/18:1(d7), showing good linearity (R² = 0.9921) across a concentration range from 50 fmol to 10 pmol.[7] These results demonstrate that OAD is not only highly specific in terms of structural analysis but also suitable for quantitative applications.

Ultimately, the study demonstrated the successful application of a newly developed ion dissociation method, OAD, for structural analysis of intact lipids. OAD enables selective and sensitive identification of C=C positions within lipid acyl chains, which has been challenging with conventional CID.

Furthermore, when combined with CID, OAD allows for the comprehensive elucidation of acyl chain composition. And, as an MS/MS-based technique, OAD does not require derivatization and can be seamlessly integrated into existing analytical workflows.

Overcoming challenges along the way

Success is never simple, of course. One major obstacle was the development of a high-output neutral radical source suitable for MS/MS. Mass spectrometers operate under high vacuum, so it was particularly challenging to design a radical source that could be integrated into existing commercial instruments without compromising vacuum conditions. To overcome this, a compact radical generator based on microwave discharge was newly developed for this study. A further challenge was that it was initially uncertain whether the OAD reaction would occur at all under gas-phase conditions. The true breakthrough therefore came not only from the development of the device but also from the discovery of a new type of gas-phase chemical reaction.

Contributing greater clarity

Discovering the beauty of OAD is like switching from a low-resolution to a high-resolution telescope – what once looked like a single star now reveals itself to be a cluster of many distinct stars. Conventional methods view lipid isomers as one object, but OAD reveals their hidden structural diversity by pinpointing the positions of double bonds. This improved “molecular resolution” is essential, because even subtle differences in C=C locations can significantly impact biological function.

| OAD2 | OAD15 | |

| n-3 | -12.0364 | -54.0470 |

| n-4 | -26.0520 | -68.0626 |

| n-5 | -40.0677 | -82.0783 |

| n-6 | -54.0833 | -96.0939 |

| n-7 | -68.0990 | -110.1096 |

| n-8 | -82.1146 | -124.1252 |

| n-9 | -96.1303 | -138.1409 |

| n-10 | -110.1459 | -152.1565 |

This development will be valuable for researchers in clinical and pharmaceutical lipidomics, as lipid structure is closely related to disease mechanisms, drug response and metabolic disorders. In addition, it is also relevant to food science, where understanding lipid composition and isomer distribution contributes to nutritional research and food quality assessment.

Importantly, OAD has also been successfully applied to MALDI imaging mass spectrometry using the iMScope system. This advancement enables spatial visualization of lipid isomers in tissue sections, extending the applicability of OAD beyond ESI-based workflows. Overall, OAD holds great promise as a new standard method for lipid structural analysis and is expected to contribute significantly to future advancements in lipidomics, both in research and clinical applications.

1) Harayama T., Riezman H. (2018). Membrane lipidomics for the understanding of functional membranes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 19: 281–296.

2) Han X. (2016). Lipidomics for studying metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 12: 668–679.

3) Thomas, M.C., Mitchell, T.W., Harman, D.G., Deeley, J.M., Nealon, J.R., Blanksby, S.J. (2008). Ozone-induced dissociation: Elucidation of double bond position within mass-selected lipid ions. Anal Chem. 80 (1): 303–311.

4) Baba T., Campbell J.L., Le Blanc J.C.Y., Baker P.R.S. (2016). Structural identification of triacylglycerol isomers using electron impact excitation of ions from organics (EIEIO). Anal Chem. 88 (5): 2747–2754.

5) Takahashi H., Shimabukuro Y., Asakawa D., Yamauchi S., Sekiya S., Iwamoto S. et al. (2018). Structural analysis of phospholipid using hydrogen abstraction dissociation and oxygen attachment dissociation in tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 90 (12): 7230–7238.

6) Uchino H., Tsugawa H., Takahashi H., Arita M. (2022). Computational mass spectrometry accelerates C=C position-resolved untargeted lipidomics using oxygen attachment dissociation. Commun Chem. 5 (1): 162.

7) Takeda H., Okamoto M., Takahashi H., Buyantogtokh B., Kishi N., Okano H. et al. (2025). Dual fragmentation via collision-induced and oxygen attachment dissociations using water and its radicals for C=C position-resolved lipidomics. Commun Chem. 8 (1): 148.

8) Kind, T. et al. (2013). LipidBlast in silico tandem mass spectrometry database for lipid identification. Nature methods. 10 (8): 755–758.