Hard to break but easy to degrade? Bioplastics: How do they measure up?

Setting new standards for accurately testing bioplastics’ real-world biodegradability

Dr. Harry Lerner, KU Leuven

Prof. Dr. David Schleheck, Universität Konstanz

Sascha Hupach, Shimadzu Deutschland GmbH

Markus Janssen, Shimadzu Europa GmbH

That yogurt cup after breakfast, the ice cream wrapper by the pool, the empty crisp bag after movie night – plastic packaging is everywhere. Versatile and convenient, it comes with a downside: Slow to degrade, it leaves behind microplastics that burden ecosystems and the food chain. Bioplastics made from renewable resources are considered a sustainable alternative. But do they actually decompose as rapidly outside the laboratory as promised? A research team at the University of Konstanz has developed a method to accurately measure biodegradability under real-world conditions – setting new standards for sustainable materials.

Everyday plastic – hidden risks

Plastic is present in almost every corner of our lives. Its strengths, such as durability and toughness, become harmful to the environment if it doesn’t fully degrade. Instead, tiny micro- and nanoplastics are released, threatening delicate ecosystems and our health. Microplastics have already been detected in human tissues, including the placenta and the brain. The full impact on health remains unknown. On top of that, traditional fossil-based plastic production has a heavy carbon footprint.

Bioplastics: Claims vs. facts

Bioplastics made from plant oils or biomass offer a sustainable alternative: They claim lower environmental impact and higher biodegradability. Yet outside ideal conditions, many of these plastics fail to degrade fully. Accurately judging their biodegradability requires new, precise testing methods.

Getting an accurate measurement is the goal

Researchers are working to precisely measure how bioplastics break down under real-world conditions. The goal is to generate reproducible results that can be applied reliably both in the lab and directly in natural ecosystems.

Current methods, such as gravimetric techniques or respirometers, aren’t well suited for in-depth analysis of biological decomposition. While enabling parallel measurements, these methods often need large samples (sometimes over 100 g), bulky equipment and plenty of space for incubators and other equipment. They also often fail to capture a complete carbon balance.

The research team at the University of Konstanz has tackled these challenges and devised a scalable, compact method. It works with much smaller samples while delivering more precise, reproducible results.

Using mineralization to measure sustainable degradation

Mineralization refers to how microorganisms biologically break down plastics. In this process, some of the carbon is converted into inorganic substances such as CO₂, water and minerals, while the rest is incorporated into biomass. This makes mineralization a key metric for fully characterizing the biological decomposition of a plastic.

Where gravimetric methods only measure leftover plastic, mineralization provides precise data to reveal the decomposition process and the resulting end products. This makes it a crucial tool for assessing the sustainability of a material under real environmental conditions.

Experiment setup: Compact, efficient, precise

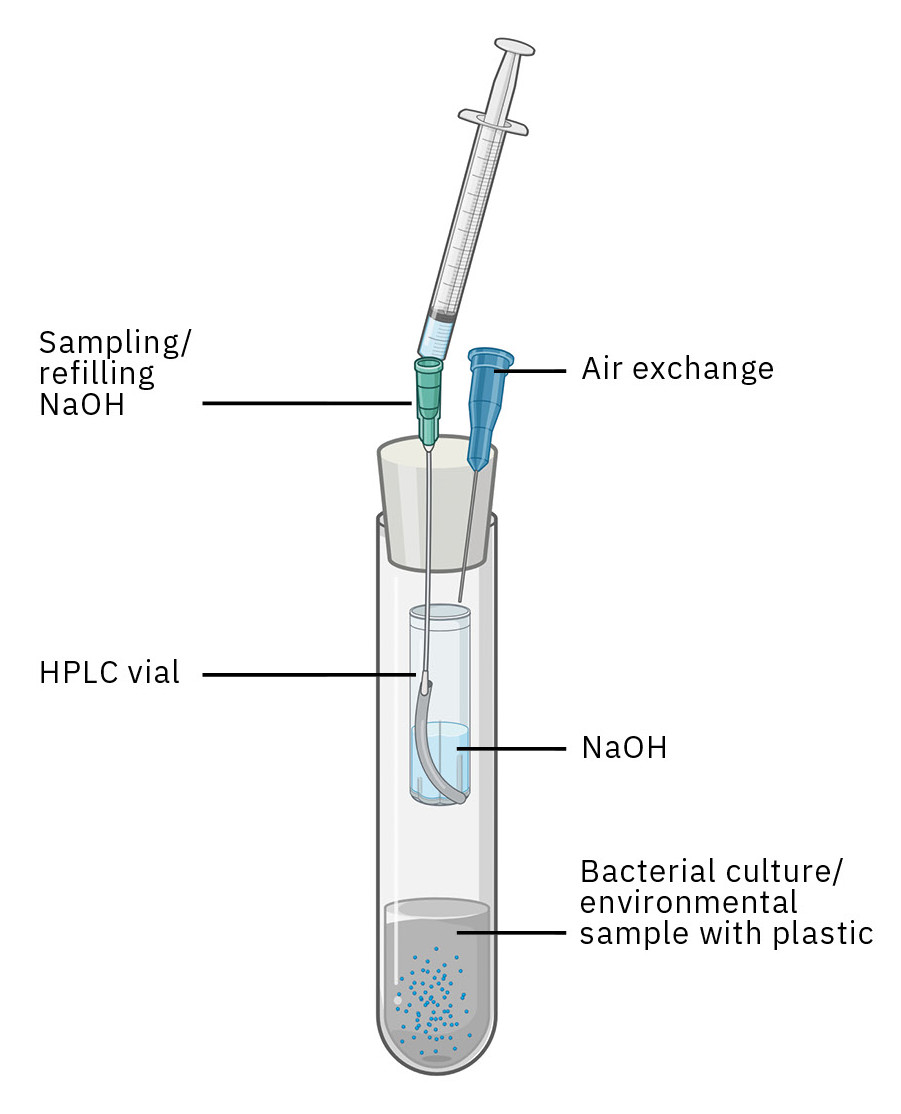

Central to the method are custom-made reaction vessels made from 15-mL culture tubes (Figure 1). Each tube holds roughly 50 mg of bioplastic along with 1 g of biological material, such as soil samples or bacterial cultures. In the tube is a small glass vial containing a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution, which chemically captures the CO₂ produced during the degradation process as carbonate.

Each tube is tightly sealed using a modified rubber stopper. The stopper has two cannulas: One is used for adding and removing the sodium hydroxide solution, while the other allows controlled gas exchange to prevent oxygen depletion. Thanks to its compact design, up to 60 tubes can fit in a standard tube rack – making it perfect for high-throughput testing.

During the degradation process, the sodium hydroxide solution is regularly removed at set intervals and replaced with fresh solution. The removed solution, containing the bound CO₂, is transferred to the Shimadzu TOC-L for TIC (Total Inorganic Carbon) analysis.

Analysis with the Shimadzu TOC-L

TIC analysis enables precise measurement of the CO₂ released during the degradation process. A diluted portion of the removed sample is acidified with phosphoric acid in the Shimadzu TOC-L. This converts the previously chemically bound carbonate back into gaseous CO₂, which is then measured with a non-dispersive infrared detector (NDIR).

This method provides a complete carbon balance: It not only captures the released CO₂ but also documents the remaining plastic mass and the formation of biomass. This approach offers a more comprehensive picture of how plastic degrades compared to traditional techniques.

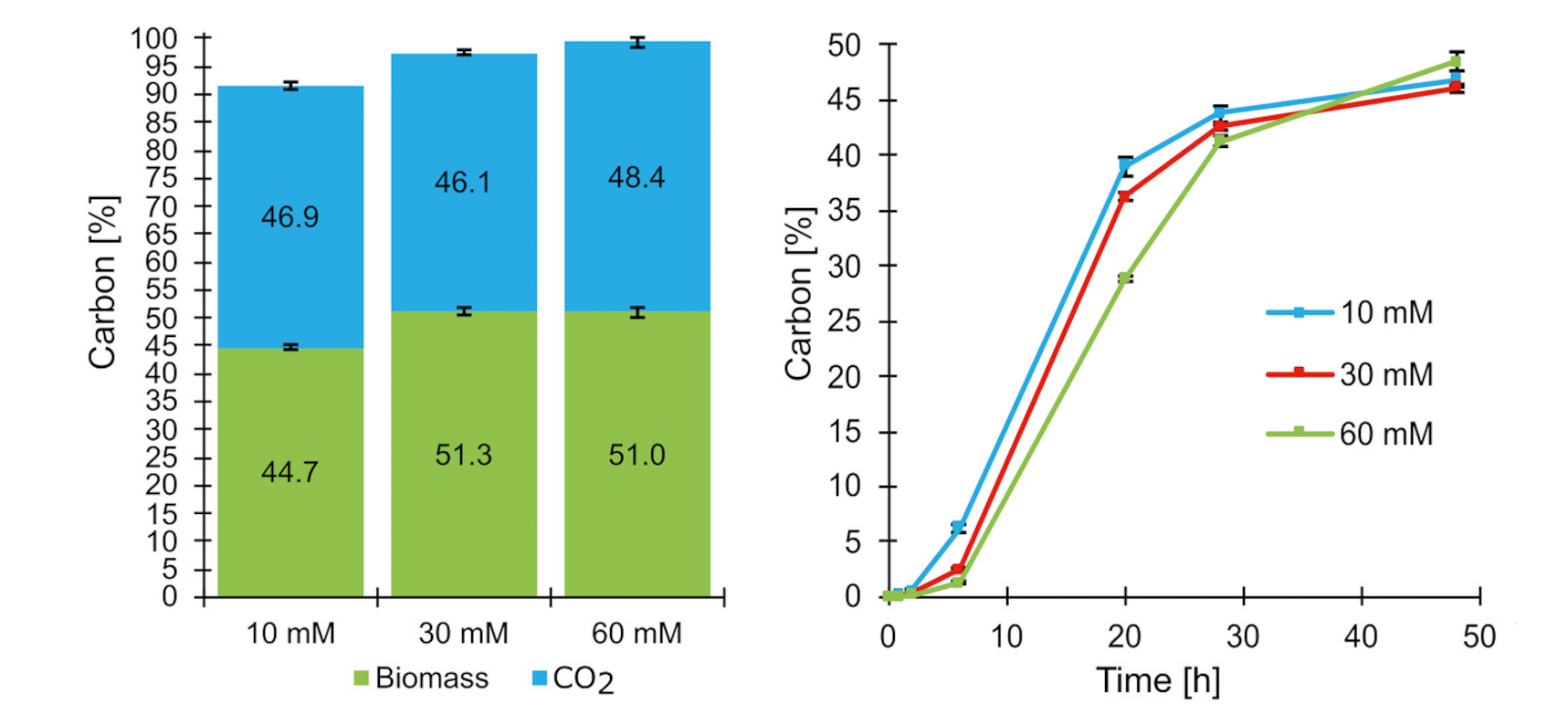

Validating the method: Glucose test

To verify the accuracy of the method, the team conducted initial experiments using glucose as the carbon source. Glucose is often applied as a reference material because its degradation products are well researched. Under ideal conditions, roughly half of the carbon should be released as CO₂, while the other half remains bound in biomass.

The experiments confirmed this prediction: The measured carbon balance matched the theoretical values, proving that the method works reliably (Figure 2).

Testing PHBV bioplastic in practice

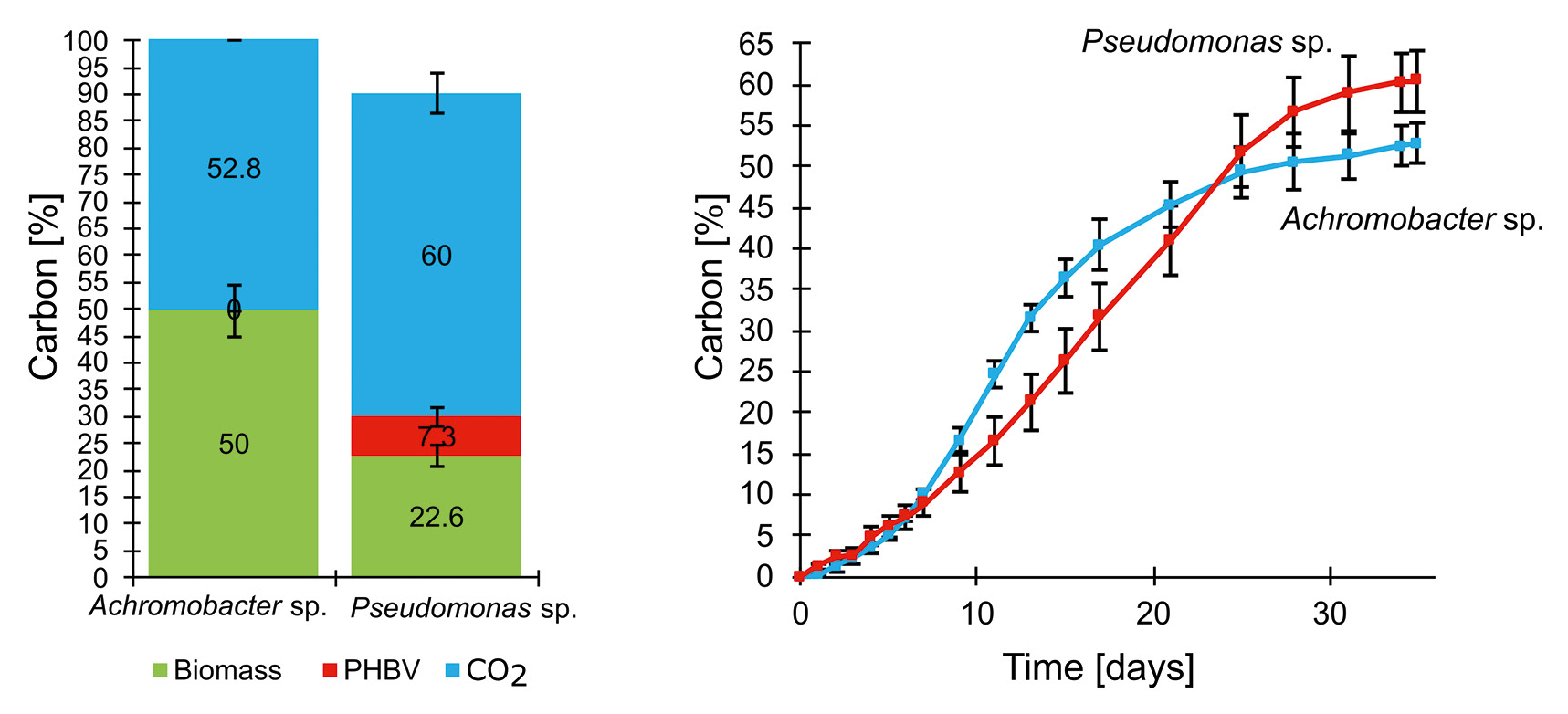

After successful validation, the team tested the method on the bioplastic polyhydroxybutyrate-co-valerate (PHBV), which is commonly used in food packaging and medical applications.

The experiments showed that PHBV could be completely decomposed under optimal conditions. Achromobacter fully degraded the plastic, while Pseudomonas left a residual fraction of less than 10 % (Figure 3). The method precisely documented the degradation process and provided valuable insights into how different bioplastics respond under specific conditions.

Precision meets sustainability

Researchers at the University of Konstanz have taken an existing method to the next level, enhancing its precision. By combining a compact reaction system with the Shimadzu TOC-L, the biodegradability of bioplastics can be measured comprehensively, reproducibly and under realistic conditions.

This research offers a proven method for systematically and thoroughly analyzing bioplastics in the future. It lays the groundwork for reliably assessing their environmental friendliness and sustainability – a crucial step to ensure that the resource cycle doesn’t end in the trash but can be effectively closed.